Humanitarian architecture

This section is designed for those who are new to humanitarian action, to provide a short overview of key aspects that affect innovation in a humanitarian setting, and pointers to where you can find more resources.

The current humanitarian system was initially set up in the wake of World War II and was substantially reformed in the 1990s and 2000s. The system is a mix of laws, legal instruments, mandated and non-mandated organisations, structures, systems and processes.

Actors

There are multiple actors in the humanitarian system. They can be generally grouped into five categories:

- UN agencies

- Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement

- Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society organisations (CSOs)

- Governments

- Non-traditional actors (everybody else!)

If you are unfamiliar with the humanitarian environment, understanding the roles of each group will help you navigate who you might work or partner with and what their role is during an emergency response. NGOs, CSOs, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and some UN agencies are the most likely to be operational on the ground, and so can be key partners for field testing ground-level innovations. You will often need to liaise with actors at both headquarters and field levels, for example, for initial authorisation or access, and then day-to-day operations and collaboration.

Sectors

Humanitarian action is primarily sector-based. The key sectors in most humanitarian responses are:

- education

- livelihoods

- food Security

- water and sanitation and hygiene

- health

- nutrition

- shelter

- protection

There are also cross-sector humanitarian interventions and services that are important for emergency response, such as the use of cash transfers (see Cash Learning Partnership).

Coordination

Ultimately governments are responsible for the rights and welfare of their citizens in the wake of an emergency. Some governments have National Disaster Management Authorities, others have different government bodies that respond. This mandate presents a challenge when governments are unwilling or unable to respond, and in extreme cases when they are the perpetrators of violence or exacerbate the impact of an emergency for their own citizens. In these cases, the UN will take on the role of leading a humanitarian response.

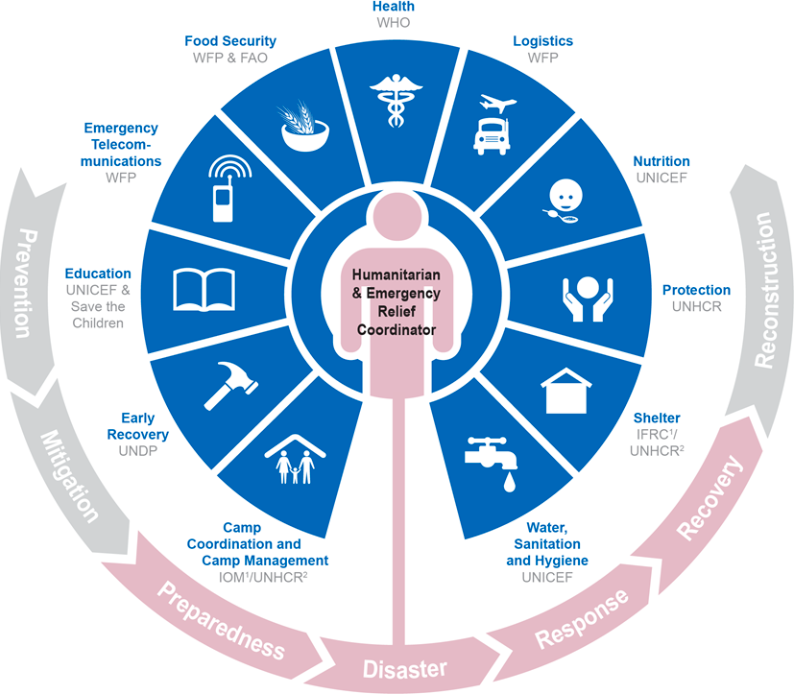

Where the UN takes the lead role, coordination of humanitarian action is the mandate of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN OCHA). In the affected country, UNOCHA’s responsible representative is the Humanitarian and Emergency Relief Coordinator. If UNOCHA are not present in country, the UN Resident Coordinator will be responsible. Globally the head of OCHA, the Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, chairs the body that coordinates all the main agencies involved in humanitarian action, called the Interagency Standing Committee (IASC).

The Cluster system

Clusters are global-level, often sector-based, groups of humanitarian organisations, both UN and non-UN, in each of the main sectors of humanitarian action; each Cluster has a lead agency or organisation whose role it is to coordinate the efforts of that sector during an emergency.

There are several additional Clusters that are not covered by the sectors outlined above, including logistics, camp management and emergency telecommunications, as well as sub-clusters and working groups for specific issues, such as those for sexual and gender-based violence and child protection that come under the Protection Cluster.

As an innovator, it is important to recognise that the Clusters not only coordinate humanitarian response, but often set the standards – both globally and in each country where they deploy for an intervention – for products or services provided.

If your innovation applies to a specific Cluster, it is vital to be aware of the current practice and standards expected, and the decisions being made with regards to a given response. It is a good idea to build a relationship with the agency mandated to lead the relevant Cluster, as they are ultimately responsible for what happens in that domain.

Emergency funding mechanisms

For rapid emergency responses that are coordinated by the UN, humanitarian funding is raised through Flash Appeals – coordinated by the UN Resident and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) in consultation with the humanitarian country team (HCT, comprising UN and non-UN partners and actors) and the affected government (though the appeals are not dependent on receiving permission from the government) – that present an early strategic response plan and can serve as the basis for a funding application to the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), among other donors.

Over longer-term programme cycles the Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) – coordinated by the UN Emergency Relief Coordinator at headquarters and Humanitarian Coordinators in the field – helps to plan, coordinate, fund, implement and monitor the response to disasters and emergencies, in consultation with governments.

The CAP fosters close cooperation between host governments, donors, aid agencies, and in particular between NGOs, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, IOM and UN agencies, to produce a Common Humanitarian Action Plan (CHAP), which serve as the foundation for Consolidated Appeals, which are launched globally by the UN Secretary-General before the beginning of each calendar year. Funding that is committed by institutional donors to these appeals can be tracked on UN OCHA’s Financial Tracking System.

The closer funding comes to reaching the amount requested, the more likely agencies will have sufficient funds, and staff will be able to work on and absorb innovations. Understanding which agencies are part of the CHAP can help you understand which agencies you may be able to collaborate with.

Funding for humanitarian interventions primarily flows through sectors. This means that if your innovation is directly associated with a problem that is identified in one of these sectors, there is more chance of funding for the development of the innovation, and funding for the scaling and long-term use of the innovation.

If your innovation does not fit into one of these sectors, then the funding, support and adoption of your innovation is likely to be more difficult. If you are developing an innovation that is applicable across multiple sectors (known as sector ‘agnostic’ or ‘cross-cutting’) then your best strategy may be to focus initially on just one or two sectors to get the funding and traction you need to develop your innovation.

However, wherever possible you should use a systems-thinking approach that looks at problems across and beyond sector approaches and can bring these sectors together in a way that develops more holistic solutions, even if you enter the problem space through one of the existing sectors.

Civil–military coordination

National and international military, state and non-state armed actors are often involved in humanitarian crises. They may be the cause of the crisis through being parties to a conflict, or they may be responding to a natural disaster, using military assets to assist with relief operations, or they may be a mandated peacekeeping force. Coordination between humanitarian actors (eg, NGOs) and these different types of military and armed actors is fraught with difficulty. They can pose a danger, or support peace; they can be seen as ‘the enemy’ by the local population or seen as ‘saviours’.

Further resources

UN OCHA (2015) Civil-Military Coordination Field Handbook

[A guide to understanding of civil–military issues]

World Vision International (2008) HISS-CAM Decision Making Tool

[A tool to help you think through difficult operational and policy decisions you may face when interacting with military and other armed actors]

UN OCHA (no date) International Humanitarian Architecture

[ A briefing on the international humanitarian architecture]

Save the Children UK (no date) Key messages in Humanitarian Response, Kaya

[A great video series covering Do No Harm, Child Safeguarding, Gender Equality in Emergencies, GBV, Infant and young children feeding in emergencies, Code of Conduct, Sphere Minimum Standards, Child Protection, Protection, Psychosocial support and Humanitarian Burnout]

Humanitarian Leadership Academy (no date) Humanitarian Essentials, Kaya

[A free e-learning course introducing the foundations of humanitarian response]

Transforming Surge Capacity Project (no date) The Humanitarian Sector

[A free e-learning course looking at the humanitarian sector and how it has evolved over time. It also introduces key guiding principles that are applicable to emergency response work]

All In Diary (AID)

[A series of one-page briefings on different aspects of the humanitarian sector, with pointers to further reading resources]

Building a Better Response (BBR)

[An online course based on interactive scenarios and including an introduction to Sphere principles and standards]

DisasterReady.org

[More than 600 training resources covering core topics such as humanitarianism, programmes, operations, protection, staff welfare, management and leadership, staff safety and security, and soft skills]