“The world today spends around US$ 25 billion to provide life-saving assistance to 125 million people devastated by wars and natural disasters…Over the last years conflicts and natural disasters have led to fast-growing numbers of people in need and a funding gap for humanitarian action of an estimated US$ 15 billion.”

These words, taken from a report by the High-Level Panel on Humanitarian Financing (2016), demonstrate the pressing need to find more effective and more efficient ways to address the needs of crisis-affected populations.

Some of this change may come through high-level policy initiatives, but it also requires that humanitarian actors continuously search for new ways to address problems in an ever-changing global environment.

What is humanitarian innovation?

For the purposes of this Guide we use the HIF–ALNAP (Obrecht and Warner, 2016) definition of innovation as:

“An iterative process that identifies, adjusts and diffuses ideas for improving humanitarian action.”

The humanitarian sector has always relied on the determination and ingenuity of those on the front line working to deliver life-saving aid to communities affected by conflict or natural disaster. But while reactive innovation has always been central to humanitarian action, the systematic application, study and implementation of proactive innovation is recent, linked to wider shifts in humanitarian actors’ application of innovation management theories from outside the system (Obrecht and Warner, 2016).

The starting point for this shift was a growing recognition that “much ongoing work in the realm of humanitarian learning and accountability does not seek to generate new and different ways of operating. Rather, it focuses on existing practices, policies and norms of behaviour, and involves detecting and correcting deviations and variances from these standards, or finding ways in which standard operating procedures can be better implemented” (Ramalingam, Scriven and Foley, 2009).

How is innovation different to standard programming?

In contrast to standard programming, innovation is a process of creative problem-solving that seeks to generate new and improved ways of operating – questioning existing practices, norms, policies and rationales – and to contribute to lasting positive change in how assistance is delivered and how communities can become more resilient. It involves a large degree of uncertainty, and significant learning to overcome gaps in knowledge and evidence.

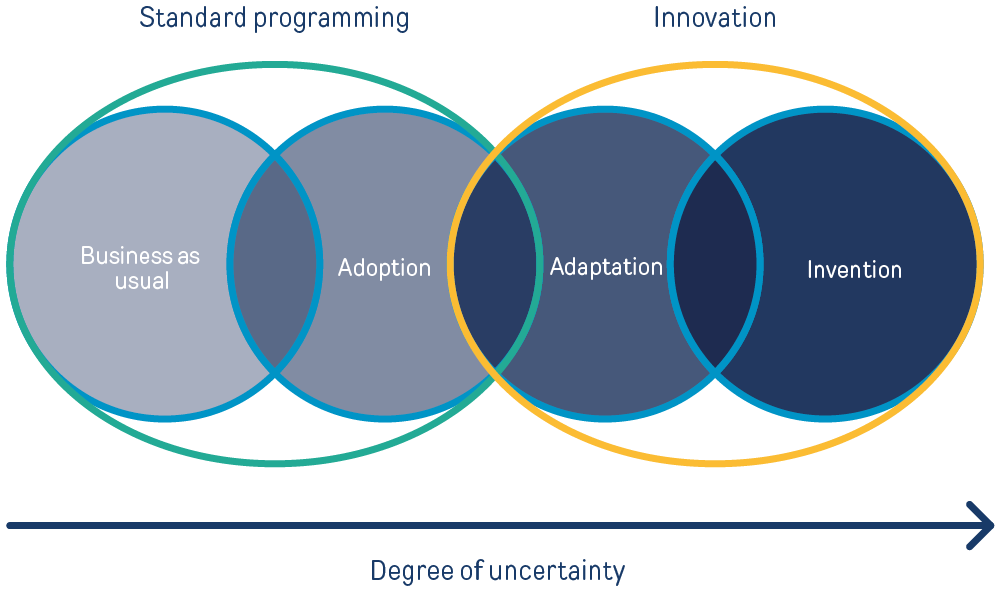

Building on our work with ALNAP (Obrecht and Warner, 2016), the diagram below presents standard programming and innovation along a continuum, with an increasing degree of uncertainty in the programme theory and expected results, and where:

- Business as usual = continuation current practice

- Adoption = implementation of a solution previously used in a similar humanitarian context which closely fits the requirements of the problem

- Adaptation = implementation of a solution which might have been used in a very different context, or originated outside the humanitarian sector, and therefore requires significant changes to be made

- Invention = generation of a new solution, where no other feasible solution to solve the problem can be identified

How can innovation thinking be applied?

Innovative ideas come in all shapes and sizes. The ‘4 Ps’ model outlined by Francis and Bessant (2005) provides a good framework for understanding four broad types of innovation:

- Product/service innovation – a change in what is offered, eg, developing culturally-appropriate menstrual hygiene management (MHM) kits (see IFRC’s MHM Kit)

- Process innovation – a change in how a product or service is created or delivered, eg, developing a user-centred design approach to delivering sanitation services in emergencies (see HIF Rapid Community Consultation Challenge )

- Position – a change in how a product or service is targeted and delivered, eg, detection and screening of severe acute malnutrition by mothers/caregivers, rather than community health workers (see Action Against Hunger’s bracelet for measuring malnutrition)

- Paradigm – a change in the underlying mental models that govern our approach, eg, encouraging a structural shift towards local manufacture of necessary relief items rather than importing ready-made items, often a key feature of the humanitarian supply chain (see Field Ready’s use of 3D printing techniques)

As described by Bessant: “Within each of these dimensions innovations can be positioned on a spectrum from ‘incremental’ – doing what we do but better – through to ‘radical’ – doing something completely different. And they can be standalone component innovations or they can form part of a linked ‘architecture’ or system which brings many different components together in a particular way.”

It is easiest to think about products/services and processes as our starting point, with innovations frequently taking on multiple characteristics and continuing to evolve over time:

- A new product might require new processes to support it (eg, IFRC).

- A new process might lead to a new product (eg, HIF Challenge).

- A new product might enable a change in how it is positioned (eg, Action Against Hunger).

- A new product and process might inspire a fundamental rethink of how humanitarian aid is delivered (eg, Field Ready).

It is important to note that technology does not equal innovation, although it has often driven innovation by providing the enabling conditions and the vehicle through which products, processes, positions and paradigm shifts can be imagined, produced and delivered. As the humanitarian innovation agenda has evolved, there is an increased un-coupling of technology and innovation, and recognition that this can only be part of the solution.

What does successful innovation look like?

Lastly, as identified through research on the HIF portfolio (Obrecht and Warner, 2016), a successful humanitarian innovation process is one that leads to:

- Consolidated learning and evidence: new knowledge is generated, or the evidence base enhanced around the area the innovation is intended to address, or around the performance of the innovation itself

- An improved solution for humanitarian action: the innovation offers a measurable, comparative improvement in effectiveness, quality, efficiency or impact over current approaches to the problem addressed by the innovation

- Wide adoption of an improved solution: the innovation is taken to scale and used by others to improve humanitarian performance