Imagine that you have to persuade your manager to give you the time and space to work on the issue you’ve uncovered, or that you have to persuade a donor to fund your project. What would you say? One way to think about this is to make the case for ‘What’s at Stake’.

This activity will help you make the case as to why your problem is important to solve, including an articulation of the value-add (What are the potential benefits of responding?) and accounting for the consequences of inaction (What are the implications if we don’t act?). You will need to articulate this from both the problem holder’s perspective, and from your organisation’s perspective.

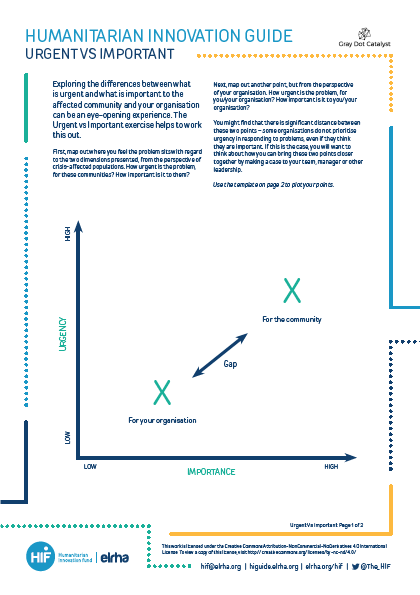

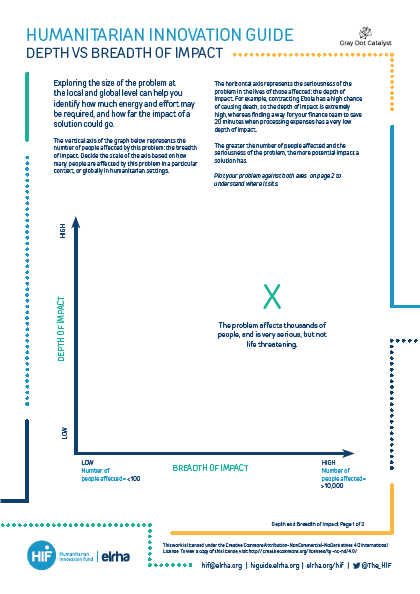

Take about 15 minutes to consider the following questions, and write down answers using the information you have put together in the Breadth and Depth of Impact and Urgent vs Important exercises (one per sticky note):

From the perspective of your organisation: what is the most important reason for responding to this challenge? What would be most concerning to your organisation if you did nothing? Write down one answer for each question.

(Hint: this is about the value-add of the potential solution. For example: ‘Because this is aligned with our operational mandate to serve X community’, or ‘If we don’t respond, inefficiency in X and Y areas continue, which will increase costs in other areas of operation over time.’)

From the perspective of the user: what’s the most important reason for responding to this challenge? What would be the consequences for both of them if we did nothing? Write down one answer for each question.

(Hint: this is about the value-add of the potential solution. For example: ‘We need to respond to this problem so that malnourished children can avoid the negative repercussions of psycho-social trauma at home’, or ‘If we don’t respond, asylum seekers will be exposed to additional security threats while on the move, in transit countries.’)

Next, you’ll want to share your answers with the rest of the group, going around the table. At this point, someone should be collecting the questions and placing them up on a wall where everyone can see.

After the questions are up on the wall, you should start grouping the responses together, conceptually, identifying emerging patterns and themes. Group all the responses into these four categories:

- Reasons for your organisation to find a solution

- Potential consequences of not finding a solution

- Reasons why it is important for the user that there is a solution

- Potential and/or actual consequences for the user if there isn’t a solution found or developed

Then take a dot sticker (two per person) and vote for the most convincing answer from the point of view of your organisation and from the point of view of the affected population.

We would recommend mapping the final categories on the ThoughtWorks Criteria for Problems Framework to visualise the different categories and their importance.

When doing this exercise, we tend to find that sometimes the initial responses aren’t always the ones that are voted on in the end. While all of the suggestions are important to consider, you will have to really hone in on the most convincing for your Challenge Brief!