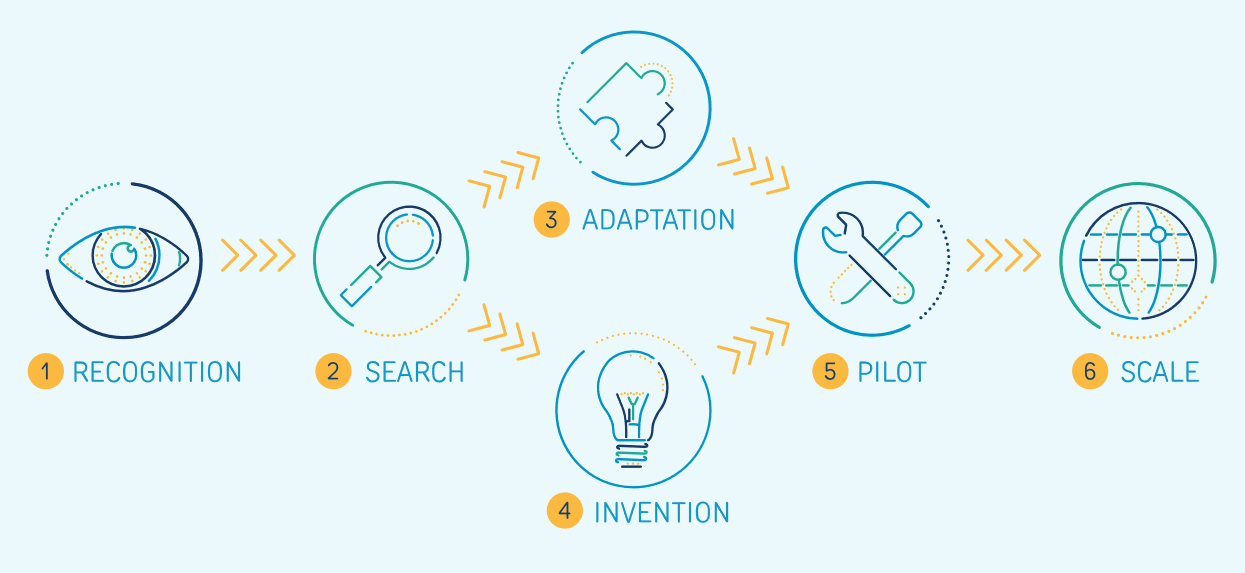

The innovation process acts as a map that will help you to identify where you are on your innovation journey, what milestones you need to reach, and what tools or approaches you can use to navigate the different stages.

There are many different innovation processes used by different organisations and derived from different schools of thought. Based on extensive learning from the HIF’s work funding and supporting humanitarian innovation, a review of over 200 relevant documents, and close analysis of 57 prioritised resources, we outline a process that we think is right for innovation in the humanitarian sector.

- Recognition – Recognition of a specific problem or opportunity. This stage involves identifying a problem or opportunity to respond to, collecting and assessing readily available knowledge on the issue and context, diagnosing root causes and properly framing the challenge.

- Search – Search for existing solutions to the problem. This stage involves looking for solutions that might already exist in the context, in the wider humanitarian sector and in other sectors or industries.

- Adaptation – Adaptation of a solution from elsewhere that requires significant rethinking of certain elements. This stage involves identifying the changes that are required to adapt an existing solution to a new context.

- Invention – Invention of a solution through the generation of new ideas. This stage involves working with users and primary beneficiaries (whether crisis-affected populations or humanitarian workers) to design a solution and develop a prototype.

- Pilot – Testing a potential solution to learn whether and how it works in a complex real-world environment. This stage consists of three workstreams: implementing your innovation, developing learning and evidence, and providing support and logistics.

- Scale – Scaling the impact of an innovation to better match the size of the social problem it seeks to address. This stage involves building in the complexity required for a sustainable innovation and distilling this complexity to make it replicable.

The World Food Programme’s mobile Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping (mVAM) project uses mobile surveys to make real-time assessments of food insecurity possible in conflict zones. This is what the innovation process looked like for the mVAM team.

mVAM was developed because WFP were increasingly being asked to work in insecure and conflict settings where access to refugee camps was not always possible or safe. In DRC, for example, their teams lacked regular and safe access to camps in Goma due to fighting along access routes. When they did get access they noticed that many people had mobile phones, which might enable remote needs assessment (Recognition).

The mVAM team carried out extensive research on existing solutions, as well as on the contextual challenges and possibilities of remotely surveying internally displaced people (IDPs). They knew that the World Bank had piloted remote phone surveys and had heard of Von Engelhart’s ‘Listening to Dar’ initiative. mVAM successfully brought in experts from multiple fields to inform their process of ideation and scoping of possibilities, and made active use of blogs and social media to raise awareness of their work and make new connections (Search).

The team experimented with voice call surveys, computer assisted telephone interviews (CAIT), SMS text surveys, and with automated interactive voice response (IVR) surveys, initially on colleagues and friends. They tested hundreds of different of wordings to increase clarity and concision to reduce surveys to a maximum of ten minutes (Invention).

In the pilot phase mVAM had to adapt to changing contextual and user demands. The Ebola crisis created a stark need for remote surveys as it was impossible to conduct face-to-face surveys. Survey respondents generated an unanticipated demand for an interactive service. Their helpline for use in Niger underwent a two-year testing process, during which mVAM partnered with Nielsen and Tulane University on methodology and evaluation (Pilot).

mVAM was able to benefit from the scale and reach of the WFP operations worldwide – providing an internal route to scale through replication in other WFP programmes in other countries. To help enable scale, mVAM also produced a suite of guidelines and tutorials including an online course. Their work has been documented in journal articles, sector reports, and media articles, all of which are logged and available from a project resource portal. mVAM is now used in more than 40 countries to conduct in excess of 20,000 surveys per month every month, with a grand total of 481,113 completed surveys to date (Scale).

We recognise that this model is not perfect, but we have sought to balance two key issues. First, to design a process that is both grounded in wider innovation theory and practice but reflects the maturity of innovation in the humanitarian sector. Second, to make it as simple as possible so that there are fewer ‘stages’. These do not necessarily align with every funder’s model of innovation, and the reality is far more messy and iterative. We hope, however, that the model is easily remembered.

The stages in this Guide represent an evolution of the HIF’s model of the innovation process. We have:

- added a new stage on Search to help identify the solutions that might already exist to address your problem, and therefore avoid unnecessary duplication;

- introduced Adaptation alongside the Invention stage to focus on innovations driven by adaptations of existing products and processes rather than the invention of new ones;

- removed the Development stage, reflecting understanding that the types of design and planning activities involved are often deeply intertwined with both invention, adaptation and pilot testing; and

- renamed the Implementation and Diffusion stages, to Pilot and Scale respectively, to reflect evolving use of common terminology across the sector.

Although this process is mapped out as linear, few if any innovation journeys are linear and chronological: most innovators will find themselves having to miss steps, go back to earlier stages and iterate over and over.

If you are lost or run into an obstacle in the middle of an innovation journey, we recommend that you use this more as a map to guide your thinking than a process to dictate your project. Identify the stage you are currently at and use the tools and guidance to help you navigate to the next stage or show that you need to go back and iterate.

For each activity in each innovation stage, we have highlighted key things to consider in relation to the Enabling Factors or Humanitarian Parameters, and we suggest that you read the briefings thoroughly as you move further along. Each stage contains a set of modules and activities that are orientated towards one or more innovation ‘milestones‘. Drawing on our learning with ALNAP (Obrecht and Warner, 2016), these are the key outputs that you need to produce to demonstrate progress in the innovation process.

Throughout the Guide we have also included real-world case studies and hypothetical examples which bring to life some of the ideas, and – although we’ve tried to limit the amount of jargon that we use – we have included a glossary of key terms.